How to Keep Patients Infection Free

Posted: July 31, 2013 Filed under: Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Safety | Tags: APIC, CDC, Infection prevention, Leadership, Lynne Karanfil, Medical Education, MedStar Health, Patient Safety Leave a commentFollowing are thoughts on the value of infection control and prevention by guest author, Lynne V. Karanfil, RN, MA, CIC, Corporate Director, Infection Prevention, MedStar Health-Corporate Quality & Safety, Faculty Associate|National Center for Human Factors Engineering in Healthcare

Joint Commission requires every hospital to have an infection control program. Most of those programs are led by an infection preventionist (IP), formerly called an infection control professional. This person is usually a nurse, microbiologist or epidemiologist, and occasionally a physician who has received additional training in preventing infections.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) has just celebrated its 40th anniversary. During the annual APIC conference in June, leadership recognized the importance of infection control in hospitals in their opening session. Following are a few highlights from the speaker’s presentations. (For more information on APIC, and for a history of infection prevention, click here to visit their website).

CDC’s Dr Arjun Srinivasan, Associate Director for Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Programs, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion indicated it is fine to monitor infection rates but asked, “What do the numbers actually mean, and how do we use those numbers to guide change?” He shared that guiding this change usually falls under the role and responsibility of an infection preventionist. He advised the audience that, “This is the time for infection prevention”, and challenged those leading change to move these efforts forward throughout the next decade. He also talked about the value of Antibiotic Stewardship, sharing that we are quickly running out of effective treatments for resistant organisms. Prevention, he shared, is what remains. Prevention is one tool we can always improve upon, and we need to do whatever we can to prevent these multi-drug resistant organisms from causing harm to patients. That we can’t stand by and watch our patients die from infections we can’t treat, especially when they could have been prevented in the first place.

Denise Murphy, RN, MPH, CIC, and Vice President, Quality and Patient Safety Main Line Health System went on to describe the “people bundles” that can help prevent infections. People bundles are safety behaviors and tools that help enforce these prevention efforts, such as:

- Paying attention to detail

- Speaking up for safety

- Stopping the line

- Empowering members to challenge folks when they are not doing the right thing.

To truly prevent adverse events and infection, we need to study what causes people to make errors, or unable to comply with safety guidelines, she emphasized.

So how are we going to make a hospital stay safer for our patients? We need to take responsibility for our own health, all of us whether patient or caregiver. Every healthcare provider needs to own his or her behavior, and speak up for safety when witnessing anything that could endanger a patient. If you as a patient, or healthcare worker, see a provider that fails to wash his or her hands, or practice hand hygiene, say something! Leaders also need to hold staff accountable.

Each hospital needs a champion to lead this work. We can prevent many infections but we need the infrastructure to do this job well. And as Patti Grant RN, BSN, MS, CIC, current APIC President indicated in her speech at the conference in Ft Lauderdale ……the public needs to demand the presence of infection preventionists in hospitals!

From my perspective, we are doing battle today. Our enemy is healthcare associated infections and the organism that cause these infections. Public enemy #1 is C difficile, an easily transmittable organism that causes unrelenting diarrhea. And then there is the resistant bacteria like carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae, most commonly E. coli and K. pneumonia, that have virtually no treatment and a high mortality for bloodstream infections. To do battle you need appropriate resources, which include knowledgeable people and the right equipment. The time is now to arm our healthcare providers with what they need to prevent these infections altogether.

The Future of Storytelling — Big Screen and Small

Posted: July 24, 2013 Filed under: Patient Centered Care, Storytelling | Tags: @FastCoCreate, Fast Company, Filmmaking, George Lucas, Hugh Hart, Lisa Cron, Movies, Stephen Spielberg, Storytelling, The Lewis Blackman Story, Wired for Story Leave a commentHugh Hart (@hughhart) recently wrote an article for Fast Company (@FastCoCreate), Movie Meltdown, $100 Tickets, And Dream Control: Lucas and Spielberg Forecast The Future Of Entertainment. In the piece, Hart shares eleven predictions made by the two storytelling geniuses, illuminating what the future of the big screen might, and might not, look like.

Becoming part of the movie, tapping into dream-tainment, games melding with movies and sensors taking the place of joysticks, controllers and devices insert audience members directly into the movie-going experience in the not too distant future. Big movies will garner higher ticket prices. Niche audiences will support indie filmmaking careers. I like the sound of this —

But what will remain unchanged is the need for good stories. As Spielberg says,

…show business, past, present, and future, depends on stories worth telling. “The thing I emphasize to everybody who comes to work at my company is, don’t play with the toys until you have something to say.”

As I prepare for a talk to be given at the National Quality Colloquium’s Innovation Track this September (Using Storytelling to Change Behavior), I have been pouring through reading on the topic of story, and how it can help change behavior. Having been part of the team that created the Tears to Transparency series, I am continuously reminded first-hand just how powerful patient stories are — to providers, as well as patients. Every time we share Lewis’ or Michael’s story–stories of harm at the hands of those entrusted to care for them–it is visibly apparent that medical students, residents, care providers and patient advocate audiences alike all feel the weight of the families’ loss. From the tears shed to the gratitude expressed for sharing these stories, a collective desire to do better for all patients permeates the room.

Most recently, I’ve been reading Lisa Cron’s (@LisaCron), Wired for Story, which has not only provided a number of pearls for my talk, but also a reminder of just how powerful the brain is in creating its own, very real, physiologic reality when engaged in reading or watching a story unfold. According to Cron’s research, stories–when told by writers who understand how to create characters we can relate to, and then place them in a world that provides just the right combination of conflict, resolution and reward–supply a pure dopamine rush to the reader, an almost addictive reward in itself.

Most recently, I’ve been reading Lisa Cron’s (@LisaCron), Wired for Story, which has not only provided a number of pearls for my talk, but also a reminder of just how powerful the brain is in creating its own, very real, physiologic reality when engaged in reading or watching a story unfold. According to Cron’s research, stories–when told by writers who understand how to create characters we can relate to, and then place them in a world that provides just the right combination of conflict, resolution and reward–supply a pure dopamine rush to the reader, an almost addictive reward in itself.

We have written about the “how tos” and “whys” re:the use of story in healthcare a number of times (see Storytelling Tips from the Pros, Developing Storytelling Skills via TEDxEaling, Storytelling and the Reality of Medicine, Using Storytelling…to Develop Empathy, The Power of Storytelling in Medicine). As a fan and student of good stories, I am not surprised at the mounting research and resources teaching craft. Research studies, mainstream authors and marketing gurus all point to the innate need we all have to make sense of life via stories. Stay tuned for more advice from the pros.

Preventing Failure to Rescue

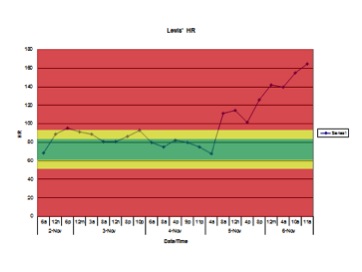

Posted: July 19, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Leadership, Medical Education, Medical Error, Patient Safety | Tags: Between the Flags, Cerner, Cliff Hughes, Clinical Excellence Commission, Failure to Rescue, Masimo Leave a comment Having co-produced the patient safety educational film “The Faces of Medical Error…From Tears to Transparency: The Story of Lewis Blackman”, I have little doubt I have seen the film more than anyone else. I viewed the film once again at a recent patient safety meeting attended by Helen Haskell, Lewis’ mother, who led an interactive, educational discussion afterwards. As many times as I have seen the film, I am repeatedly shocked and saddened when the chart showing Lewis’ heart rate over the last 48 hours of his life appears on the screen.

Having co-produced the patient safety educational film “The Faces of Medical Error…From Tears to Transparency: The Story of Lewis Blackman”, I have little doubt I have seen the film more than anyone else. I viewed the film once again at a recent patient safety meeting attended by Helen Haskell, Lewis’ mother, who led an interactive, educational discussion afterwards. As many times as I have seen the film, I am repeatedly shocked and saddened when the chart showing Lewis’ heart rate over the last 48 hours of his life appears on the screen.

The faces of those in the audience reflect similar horror. The significant elevations in heart rate combined with the numerous changes in Lewis’ condition are so obvious to all of us in the audience playing “Monday morning quarterback”. We assume that those taking care of Lewis that weekend weren’t bad doctors or nurses. That they were all caring and compassionate, trying to do the best for Lewis, their patient…and yet they missed so many obvious warning signs predictive of pending doom. Why did this “inability to see the obvious” — or Failure to Rescue — happen with Lewis, and why does it continue to occur across the country with patients suffering similar harm?

Failure to Rescue is a well-known term in the patient safety arena. It is recognized as one of the more frequent and challenging causes of harm to patients around the world. Defined by the Association for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ), failure to rescue is:

…shorthand for failure to rescue (i.e., prevent a clinically important deterioration, such as death or permanent disability) from a complication of an underlying illness (e.g., cardiac arrest in a patient with acute myocardial infarction) or a complication of medical care (e.g., major hemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction). Failure to rescue thus provides a measure of the degree to which providers responded to adverse occurrences (e.g., hospital-acquired infections, cardiac arrest or shock) that developed on their watch. It may reflect the quality of monitoring, the effectiveness of actions taken once early complications are recognized, or both.

Human Factors colleagues remind us every day that humans are going to be human, and will make mistakes each and every day. They continue to tell us that until we build systems that take human tendencies out of the equation, we will continue to ask the impossible of our care teams, continue to put patients at risk, and continue to create clinical care environments that are doomed to fail.

To this end, there may be some good news on the horizon. Healthcare technology companies like Masimo and Cerner are making Failure to Rescue a top priority. Human Factors experts are now part of the conversation aimed at finding solutions. In addition, innovative safety leaders like Professor Cliff Hughes, the Chief Executive Officer at the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC) in New South Wales, Australia, along with his CEC colleagues, have been redesigning clinical care models that are now showing early successes in preventing Failure to Rescue. Cliff has been a regular attendee at our Telluride Patient Safety Roundtable. He has also been long-time friend and wonderful mentor to me, and many others, over the years. The CEC program, called “Between the Flags“, “is designed to establish a ‘safety net’ in all NSW public hospitals and healthcare facilities that reduces the risks of patients deteriorating unnoticed and ensures they receive appropriate care in response if they do”.

The Program uses the analogy of Surf Life Saving Australia’s Lifeguards and Life Savers who keep people safe by ensuring they are under close observation and rapidly rescue them, should something go wrong. The Between the Flags Program has a Five Element Strategy, which is essential to its long-term sustainability.

- A governance structure in each Local Health Network and hospital in NSW to oversee the implementation and sustainability of the Program.

- Standards for the criteria used for early recognition of the deteriorating patient (clinical observation and ‘track and trigger’ system), incorporated in standard observation charts e.g. the Standard Adult General Observation Chart (SAGO).

- Standards for a process for escalation of concern and rapid response to the deteriorating patient (Clinical Emergency Response System).

- Education packages for all staff to give them the knowledge and skills to confidently recognise and manage the deteriorating patient.

- Standards for key performance indicators to be collected, collated and used to inform the users of the system and those managing the implementation and continuation of the Program.

More on the Between the Flags program, diagnostic errors, conformational bias, premature closure and other issues related to Failure to Rescue in Part II…

Patients Are Waiting to Partner: Invite Them to Participate

Posted: July 16, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Medical Error, Patient Centered Care | Tags: Baltimore Sun, Marie McCarren, Patient Education, Patient partnership Leave a commentIn a recent Baltimore Sun piece, healthcare writer Marie McCarren wrote an op-ed providing “A prescription for fewer medical errors” — reflections from an emergency room visit with her husband that later turned into a stay on the intensive care unit. McCarren emphasized the need for healthcare providers to work at clearly communicating the ways in which family members of patients can help make care safer. She advises healthcare executives create meaningful patient handbooks that provide clear ways for patients to keep track of the complicated care system at what is most often one of the most stressful times in their life. She reminds us:

…Hospital executives, please listen. We are untrained and underslept, scared and stupider than we are in regular life. And we’re passive, because we want very much to believe that the doctors and nurses have the situation under control. Exploit our weaknesses. Give us a framework that will help us come up with useful questions and essentially order us to use it. I believe it would result in fewer mistakes and shorter hospital stays…

Almost in tandem, the Association for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) released the Guide to Patient and Family Engagement in Hospital Quality & Safety, outlining the value of inviting patients and families to engage in their care, and providing a “how to” for those still unsure. The guide covers the following topics:

- Information to Help Hospitals Get Started, which addresses: a) How to select, implement, and evaluate the Guide’s strategies. b) How patient and family engagement can benefit your hospital. c) How senior hospital leadership can promote patient and family engagement.

- Strategy 1: Working With Patients and Families as Advisors shows how hospitals can work with patients and family members as advisors at the organizational level.

- Strategy 2: Communicating to Improve Quality helps improve communication among patients, family members, clinicians, and hospital staff from the point of admission.

- Strategy 3: Nurse Bedside Shift Report supports the safe handoff of care between nurses by involving the patient and family in the change of shift report for nurses.

- Strategy 4: IDEAL Discharge Planning helps reduce preventable readmissions by engaging patients and family members in the transition from hospital to home.

*For more information about the Guide to Patient and Family Engagement in Hospital Quality and Safety, contact Margie Shofer at (301) 427-1259 or Marjorie.shofer@ahrq.hhs.gov.

Many health systems have begun to create patient education and admission materials that do in fact take some of these factors into account. If you, or a loved one, are about to become a patient, be sure to ask how you can best partner with your care team. If possible, request patient education materials well before your stay and provide feedback!

We know that engaged patients have the potential to not only help make care safer, but also improve outcomes. There are many intelligent people, with a fresh outlook and vested interest in these outcomes waiting on the sidelines. If you are a care provider, find a way to invite them in. And please, share your results with us.

Creating A Culture of Safety? Start with A Patient Story!

Posted: July 10, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Just Culture, Leadership, Patient Advocacy, Patient Centered Care, Patient Safety, Storytelling | Tags: Harvard Business Review, Helen Haskell, High Reliability, John Kotter, MedStar Health, Safety culture, The Lewis Blackman Story, Transparent Health 1 Comment Every three months, Dave Mayer MD, Larry Smith and MedStar Health host a quarterly Quality, Patient Safety & Risk Management Retreat, inviting leaders and innovators across the health system to spend a morning discussing topics such as high reliability organizations, transparency and patient centered care. For the last year, two speakers–also healthcare thought leaders from across the country–have been invited to share their expertise with MedStar associates during the retreat. (An archive of retreat videos can be found on the MedStar Patient Safety & Quality website here).

Every three months, Dave Mayer MD, Larry Smith and MedStar Health host a quarterly Quality, Patient Safety & Risk Management Retreat, inviting leaders and innovators across the health system to spend a morning discussing topics such as high reliability organizations, transparency and patient centered care. For the last year, two speakers–also healthcare thought leaders from across the country–have been invited to share their expertise with MedStar associates during the retreat. (An archive of retreat videos can be found on the MedStar Patient Safety & Quality website here).

Today’s retreat included:

- Denise Murphy: A Carole DeMille Lifetime Achievement Award winner for infection prevention and now Vice President of Quality & Safety at Main Line Health in Philadelphia. She is leading her health system on the journey to becoming a high reliability organization.

- Helen Haskell: Mother, patient advocate, healthcare policy driver and founder of Mothers Against Medical Error (MAME).

Those who follow our blogs (ETY & Telluride) might already be familiar with the story of Lewis Blackman, Helen’s 15-year-old son of great promise who was taken far too soon by medical error. Helen and her family have gifted healthcare communities around the world by sharing their loss so that others can learn with the hope that similar harm can be prevented. Both speakers emphasized the need to personalize every healthcare encounter, keeping patient stories at the front lines of care. Both Denise and Helen’s presentations also have been made available on the MedStar Health website. Following are useful takeaways from this quarter’s retreat for use in your own health system.

Denise referenced John P. Kotter’s Harvard Business Review article, Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail, as a resource, and shared the following tips for successful creation of a culture of safety:

- Patient safety trumps all else

- Keep leadership uncomfortable

- Keep patient stories up front — put a face on all harm

- Leaders lead from the front versus push from behind

- Provide tools for the critical conversations patient centered care requires

- Engage all care providers in the journey

- Flatten authority gradient and reduce power distance (i.e. Everyone’s voice matters, title irrelevant)

- Include daily “Safety Huddles” to assess progress, update colleagues on patients at risk, share stories and any concerns.

And finally, here is the trailer for The Story of Lewis Blackman. If interested, there is a YouTube version of the entire film available in the creative commons, and a DVD copy available for a nominal fee that includes learning materials. If interested in acquiring a copy of the educational film please reach out.

Oliver Sacks, One of Medicine’s Best Storytellers, Shares His Story

Posted: July 3, 2013 Filed under: Medical Education, Patient Centered Care, Storytelling | Tags: Awakenings, Danielle Ofri, Films, NYU School of Medicine, Oliver Sacks, Storytelling, Writers Leave a commentIn a recent post, What Doctors Feel, I referenced the work of Danielle Ofri MD, author, Associate Professor of Medicine at NYU, and practicing internist at Bellevue Hospital in NYC, whose research, and book by the same title, examines how emotions affect those providing care. Ofri’s website (found here) provides a number of related articles, as well as the following interview with colleague Oliver Sacks. Sacks is also a physician, and a well-known author whose work includes the 1973 memoir, Awakenings, later made into an Academy Award nominated film starring Robert DeNiro and Robin Williams.

Sacks has long believed in the value of sharing the stories of his neurologically impaired patients, as well as working to make them whole again. The compassion and empathy he feels for each of the patients whose story he shares is palpable.

Please enjoy his story over the holiday week–we will be back online July 9th!