Voices from The Telluride Experience: Sydney

Posted: May 2, 2016 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Leadership, Medical Education, Nursing Education, Patient Advocacy, Patient Centered Care, Patient Experience, Patient Safety, Storytelling | Tags: Academy for Emerging Leaders in Patient Safety, Australia, Clinical Excellence Commission, Medical Education, Patient Safety, SolidLine Media, Storytelling, Sydney, Telluride Experience Leave a commentAs in Doha, SolidLine Media was along to capture the stories being told at The Telluride Experience: Sydney! Thanks to Greg, Michael, John, Ali and team for pulling this short video together utilizing movie magic across the continents in time for the Minister of Health herself to view it live in Sydney, at the Clinical Excellence Commission’s reception for students and faculty before we returned home last week.

Truly a great team effort by all to bring the reflections and voices of change to life.

Living Mindfulness

Posted: August 9, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Advocacy, Patient Centered Care, Patient Safety | Tags: Australia, Cliff Hughes MD, Clinical Excellence Commission, High Reliability Organizations, Mindfulness, Telluride Patient Safety Educational Roundtable Leave a commentThe concept of “mindfulness” dates back more than 2500 years. In Sanskrit, it means awareness that, according to the teaching of the Buddha, is considered to be of great importance in the path to enlightenment. It is said that when we are enlightened, “greed, hatred and delusion have been overcome, abandoned and are absent from our mind and we are focused on the present moment and the reality of things around us”.

With the increased focus on High Reliability in healthcare over the past few years, we continue to hear more about the importance of mindfulness as a patient safety tool. I always thought of myself as being “mindful”. Anesthesiologists have to be “in the moment”, aware of the different cues happening around us in the operating room. However, through two simple examples recently, I learned a very important lesson from a longtime friend and mentor, Cliff Hughes MD, — that being mindful and aware of our surroundings is only half of the equation when applying mindfulness to safety.

For many years, I have had the great fortune of being a close friend and student of Professor Cliff Hughes. Cliff was a cardiothoracic surgeon for 25 plus years in Sydney, Australia before being elected CEO of the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC) in New South Wales, Australia. From the CEC website:

For many years, I have had the great fortune of being a close friend and student of Professor Cliff Hughes. Cliff was a cardiothoracic surgeon for 25 plus years in Sydney, Australia before being elected CEO of the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC) in New South Wales, Australia. From the CEC website:

(Cliff)…has been chair or a member of numerous State and federal committees associated with quality, safety and research in clinical practice for health care services. Prof Hughes has held various positions in the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons–including Senior Examiner in Cardiothoracic Surgery and member of the College Council. He has been a member of four editorial boards and has published widely in books, journals and conference proceedings on cardiothoracic surgery, quality and safety. Prof Hughes has a particular passion for patient-driven care, better incident management, quality improvement programs and development of clinical leaders.

Cliff, and his lovely wife Liz, were visiting from Australia this month, in part to attend our Telluride East Patient Safety Roundtable and Summer Camp in Washington, DC. As a result, my wife Cathy and I were able to spend some social time with Cliff and LIz, and with a consummate teacher like Cliff in the mix, the learning does not stop outside the four walls of a classroom or hospital. I share the following stories because they left such an impression on me, showing me that Cliff’s wisdom comes through living that which he teaches on a daily basis…

As we were walking through a local grocery store, we came across a small puddle of water on the floor in the produce section. I walked around the puddle, pointing out the potential safety hazard to Cliff following behind me. I continued walking, and it took about twenty more steps before I realized Cliff was no longer behind me. Instead of walking around the puddle like I had, Cliff had detoured to find the produce manager and show him the puddle so the safety hazard could be cleaned up. While I was mindful of Cliff’s safety in pointing out the puddle, Cliff was mindful of all others who would be following our same path and could suffer harm by slipping on the wet floor. Cliff acted on his mindfulness, and by reporting the event, helped prevent possible harm to others. I was mindful but didn’t act.

The very next day, Cliff and I were walking through a parking lot after a quick stop at a local Starbucks. I was in deep thought about our upcoming meeting. As we walked, we passed a parked car which I vaguely noticed had a back tire that was quite low…not completely flat, but would most likely soon be so with some extended driving. Momentarily noting the car, I kept walking, thinking about our upcoming meeting, Once again, Cliff disappeared and was no longer behind me. Instead, he was standing by the side of the car with the low tire, writing on a piece of paper. I walked back to where he was standing, and asked what he was doing. He said he was writing a note to the car’s owner, alerting the driver of the possible safety concern. Finishing the note, he placed it under the windshield wiper, clearly visible to the driver. Again, I noticed the potential safety hazard but was distracted by my own thoughts and priorities, and kept walking. I wasn’t fully “in the moment”, a prerequisite of mindfulness. Cliff, however, was fully in the moment. As such, he was able to not only notice potential safety risks, but also to report each incident and act to prevent possible harm to the driver and grocery shoppers.

Two simple, but thoughtful, actions became perfect learning moments for me, role-modeled by a masterful safety “Sensui”. Mindfulness without action is stasis.

Healthcare needs more Cliff Hughes’…

Preventing Failure to Rescue

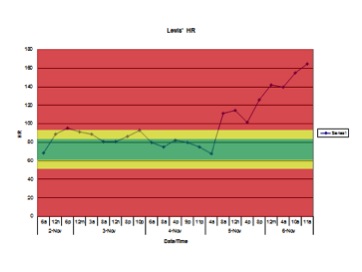

Posted: July 19, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Leadership, Medical Education, Medical Error, Patient Safety | Tags: Between the Flags, Cerner, Cliff Hughes, Clinical Excellence Commission, Failure to Rescue, Masimo Leave a comment Having co-produced the patient safety educational film “The Faces of Medical Error…From Tears to Transparency: The Story of Lewis Blackman”, I have little doubt I have seen the film more than anyone else. I viewed the film once again at a recent patient safety meeting attended by Helen Haskell, Lewis’ mother, who led an interactive, educational discussion afterwards. As many times as I have seen the film, I am repeatedly shocked and saddened when the chart showing Lewis’ heart rate over the last 48 hours of his life appears on the screen.

Having co-produced the patient safety educational film “The Faces of Medical Error…From Tears to Transparency: The Story of Lewis Blackman”, I have little doubt I have seen the film more than anyone else. I viewed the film once again at a recent patient safety meeting attended by Helen Haskell, Lewis’ mother, who led an interactive, educational discussion afterwards. As many times as I have seen the film, I am repeatedly shocked and saddened when the chart showing Lewis’ heart rate over the last 48 hours of his life appears on the screen.

The faces of those in the audience reflect similar horror. The significant elevations in heart rate combined with the numerous changes in Lewis’ condition are so obvious to all of us in the audience playing “Monday morning quarterback”. We assume that those taking care of Lewis that weekend weren’t bad doctors or nurses. That they were all caring and compassionate, trying to do the best for Lewis, their patient…and yet they missed so many obvious warning signs predictive of pending doom. Why did this “inability to see the obvious” — or Failure to Rescue — happen with Lewis, and why does it continue to occur across the country with patients suffering similar harm?

Failure to Rescue is a well-known term in the patient safety arena. It is recognized as one of the more frequent and challenging causes of harm to patients around the world. Defined by the Association for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ), failure to rescue is:

…shorthand for failure to rescue (i.e., prevent a clinically important deterioration, such as death or permanent disability) from a complication of an underlying illness (e.g., cardiac arrest in a patient with acute myocardial infarction) or a complication of medical care (e.g., major hemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction). Failure to rescue thus provides a measure of the degree to which providers responded to adverse occurrences (e.g., hospital-acquired infections, cardiac arrest or shock) that developed on their watch. It may reflect the quality of monitoring, the effectiveness of actions taken once early complications are recognized, or both.

Human Factors colleagues remind us every day that humans are going to be human, and will make mistakes each and every day. They continue to tell us that until we build systems that take human tendencies out of the equation, we will continue to ask the impossible of our care teams, continue to put patients at risk, and continue to create clinical care environments that are doomed to fail.

To this end, there may be some good news on the horizon. Healthcare technology companies like Masimo and Cerner are making Failure to Rescue a top priority. Human Factors experts are now part of the conversation aimed at finding solutions. In addition, innovative safety leaders like Professor Cliff Hughes, the Chief Executive Officer at the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC) in New South Wales, Australia, along with his CEC colleagues, have been redesigning clinical care models that are now showing early successes in preventing Failure to Rescue. Cliff has been a regular attendee at our Telluride Patient Safety Roundtable. He has also been long-time friend and wonderful mentor to me, and many others, over the years. The CEC program, called “Between the Flags“, “is designed to establish a ‘safety net’ in all NSW public hospitals and healthcare facilities that reduces the risks of patients deteriorating unnoticed and ensures they receive appropriate care in response if they do”.

The Program uses the analogy of Surf Life Saving Australia’s Lifeguards and Life Savers who keep people safe by ensuring they are under close observation and rapidly rescue them, should something go wrong. The Between the Flags Program has a Five Element Strategy, which is essential to its long-term sustainability.

- A governance structure in each Local Health Network and hospital in NSW to oversee the implementation and sustainability of the Program.

- Standards for the criteria used for early recognition of the deteriorating patient (clinical observation and ‘track and trigger’ system), incorporated in standard observation charts e.g. the Standard Adult General Observation Chart (SAGO).

- Standards for a process for escalation of concern and rapid response to the deteriorating patient (Clinical Emergency Response System).

- Education packages for all staff to give them the knowledge and skills to confidently recognise and manage the deteriorating patient.

- Standards for key performance indicators to be collected, collated and used to inform the users of the system and those managing the implementation and continuation of the Program.

More on the Between the Flags program, diagnostic errors, conformational bias, premature closure and other issues related to Failure to Rescue in Part II…

Universal Need in Medical Education: Care for the Caregiver Programs

Posted: November 5, 2012 Filed under: Just Culture, Medical Education, Patient Centered Care | Tags: Cliff Hughes, Clinical Excellence Commission, Kim Oates, Peter Carter, Second Victim, Susan Scott, University of Missouri Leave a commentI was asked to give a talk at the International Society for Quality in Medicine (ISQua) meeting two weeks ago in Geneva, Switzerland. Meetings like this are usually the choir reinforcing what we all are living and breathing and trying to teach our students and colleagues who have yet to embrace the change necessary when it comes to preventing and managing medical error in healthcare. I have found the ISQua meeting to be one of the better quality and safety annual meetings, and was honored when I was invited to be a speaker on a patient safety education panel moderated by Professor Cliff Hughes, renown cardiac surgeon and now CEO for the New South Wales Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC). The CEC has been doing outstanding quality and safety work in Australia for many years. Also on the panel were Professor Kim Oates, pediatrician and patient safety education guru from Australia, and Peter Carter, the Acting CEO of ISQua. It is always good to see friends from down under who join us each year in Colorado for our annual Telluride Patient Safety Educational Roundtable and Student/Resident Summer Camps.

During the week in Geneva, each of us addressed our different area of expertise related to patient safety education, but two universal themes we all touched upon in our talks were Just Culture and Care for the Caregiver (also known as the Second Victim). Both are important topics to be explored and developed when educating the young, as well as necessary to change the current healthcare culture. What we do after an event occurs, in many ways, defines who we are as health professionals and people. These choices impact not only our patients and their families, but our colleagues involved in the error, who are also traumatized by the event.

Albert Wu from Johns Hopkins University began raising attention to Second Victim issues a number of years ago which has led to a growing body of research in this important safety area. Because of my own interest in this area, one session in particular caught my attention this year when I was reviewing the ISQua program. The presentations and discussions were all outstanding, but as usual, there was one that especially hit home, given the point I’m at my career. This year, it was Susan Scott RN MSN, Patient Safety Officer from the University of Missouri Health Care System, who gave an excellent talk on their Second Victim program that has been in place for a few years. I encourage all who are interested in this area to become more familiar with their work, and the positive results that have come from it, as I’m not aware of any other organization that has taken Second Victim work to the level University of Missouri has under Susan’s leadership. Leadership at the health system is also fully invested in the program, and the positive results they have seen reflect that commitment.

Their program, called “for You” is a model program that lays out examples of how best to support fellow caregivers when harm occurs. Using research findings that have come from numerous caregiver support engagements, team debriefs and reflections, they have developed a three-tiered interventional model that is activated when a referral comes into the safety office. Since implementing the model, they have had over 600 team activations, or opportunities, to reach out and support their fellow caregivers in the last three years. It is because of the cutting edge work like this led by Susan, her team, and the University of Missouri Health Care System leadership, that we have examples of how to do it right for our students, as well as change the culture in our own health care organizations. To paraphrase Margaret Meade, all it takes is a small group of thoughtful and committed people to change the world for the better.

Their program, called “for You” is a model program that lays out examples of how best to support fellow caregivers when harm occurs. Using research findings that have come from numerous caregiver support engagements, team debriefs and reflections, they have developed a three-tiered interventional model that is activated when a referral comes into the safety office. Since implementing the model, they have had over 600 team activations, or opportunities, to reach out and support their fellow caregivers in the last three years. It is because of the cutting edge work like this led by Susan, her team, and the University of Missouri Health Care System leadership, that we have examples of how to do it right for our students, as well as change the culture in our own health care organizations. To paraphrase Margaret Meade, all it takes is a small group of thoughtful and committed people to change the world for the better.