Patient Advocate and Telluride Faculty Dan Ford Describes TE: CO Class of 2016

Posted: July 12, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment Over the last five days in Telluride, I have gotten to know an awesome group of 26 medical and nursing students. You clearly will play key roles in changing patient safety in constructive ways. As Dr John Toussaint (ThedaCare Center for HealthCare Value, Appleton, WI) suggests: “How can we provide high quality care unless we provide a base of safe care.”

Over the last five days in Telluride, I have gotten to know an awesome group of 26 medical and nursing students. You clearly will play key roles in changing patient safety in constructive ways. As Dr John Toussaint (ThedaCare Center for HealthCare Value, Appleton, WI) suggests: “How can we provide high quality care unless we provide a base of safe care.”

Various descriptors come to mind. Compassionate. Caring. Thoughtful. Very smart. Respectful. Self-reflective. Genuine listeners. Open to learning and sharing new ideas. Passionate. Willing to live your values in speaking up, decision making and problem solving. Mindful. Inclusive. Thirsting to know more about patient safety….and you did.

You became good friends, bonding, getting to know and care about each other as human beings without labels or titles or tribes. It is clear you are patient and team focused and became even more so during our indoor and outdoor classroom work, social times and the big hike.

Telluride and the mountains are beautiful. Y’all have an inner beauty that will continue to serve you very well in all you do.

I didn’t want our time together to end, especially when several commented that this experience has been life-changing. I am desirious of staying in touch as you take your individual learnings and feelings forward and to helping you in any way I can.

I continue to encourage you to always live and to role model your True North. You will be seriously tested.

I wish each of you many blessings! I am honored to call you friends….

12 Years and 1400 Patient Safety Leaders Later…

Posted: June 6, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 Comment Twelve years…that is how long it has been since we first traveled to Telluride, CO to kick-off our inaugural Patient Safety Educational Roundtable and Summer Camp. As we headed west again this weekend to meet with the 36 graduate resident physicians and future health care leaders who were selected from a large group of applicants, it is hard not to think back about all that has happened in those twelve years and the many who have contributed to make it happen.

Twelve years…that is how long it has been since we first traveled to Telluride, CO to kick-off our inaugural Patient Safety Educational Roundtable and Summer Camp. As we headed west again this weekend to meet with the 36 graduate resident physicians and future health care leaders who were selected from a large group of applicants, it is hard not to think back about all that has happened in those twelve years and the many who have contributed to make it happen.

Twelve years ago, those who came to Telluride believing in our Educate the Young mission consisted of patient safety leaders Tim McDonald, Anne Gunderson, Kelly Smith, Deb Klamen, Julie Johnson, Paul Barash, Gwen Sherwood, Bob Galbraith, Ingrid Philibert, and Shelly Dierking to name just a few. However, the smartest thing we ever did was invite patient advocates to the Patient Safety Educational Roundtable. People like Helen Haskell, Carole Hemmelgarn, Patty and David Skolnik, and Rosemary Gibson were active partners in our work from that first year and made our discussions more productive and our outcomes better.

Over the years, many new faculty joined us in our Educate the Young journey. Some of these additional patient safety faculty included Lucian Leape, Richard Corder, John Nance, Paul Levy, David Classen, Kathy Pischke-Winn, Joan Lowery, Roger Leonard, and Tracy Granzyk. We were also fortunate to have international safety leaders join our faculty, including Kim Oates and Cliff Hughes from Australia, who became regular attendees and popular “mentors” to the future healthcare leaders even though they had to travel almost 10,000 miles to join us each year.

Through all these years, two things remained constant – our commitment to Educating the Young and our partnership with patients. Helen, Carole, Patty, David, and Rosemary continue to be active participants each year but additional patient advocates have joined us including national advocacy leaders Dan Ford and Lisa Freeman.

Through the vision and support of Carolyn Clancy and the AHRQ, what began as a small educational immersion for twenty health science students has now exploded. We continue to grow because of the generous support of The Doctor’s Company Foundation (who provides full scholarships to close to 100 medical and nursing students each year), the Committee of Interns and Residents, COPIC and MedStar Health. This year, over 700 residents, medical students and nursing students will go though one of the Telluride Experience Patient Safety Summer Camps. Out Telluride Scholars Alumni network continues to grow – our future health care leaders staying connected through the years, sharing quality and safety project successes and learning from each other. And, for the first time, the Telluride Experience went International this past spring as we ran patient safety camps in Doha, Qatar and Sydney, Australia.

Thanks go out to the many passionate and committed faculty and others who have given so much to make our Educate the Young journey so very special. It has been an amazing twelve-year run…

Remembering Mr. Farrell and Other Fathers We Have Lost

Posted: June 21, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 CommentAs we reflect on our continued commitment to eliminating preventable medical harm, it is important to never forget the lost loved ones that help keep us focused on our important mission. On this Father’s Day, as a proud parent and even prouder grandparent, I can’t help but reflect back this morning to last year’s Telluride Patient Safety Summer Camp and the personal story Caitlin Farrell shared with all of us on Father’s Day last year. Her story is also featured this weekend on http://runningahospital.blogspot.com/ It is one story I will never forget…

Fear, Forgiveness, and Father’s Day

Published June 16, 2014 | By CFarrell

Yesterday was Father’s Day, 2014. I woke up before everyone else in my room. Rolling out of bed, I padded down the stairs and brewed a cup of much-needed coffee. Pouring my face over the steaming cup, I looked out my window to the inspiring landscape of endless white-capped mountains. This year marks the ninth Father’s Day that I have spent without my dad, but the mountains and my purpose this week made me feel as though he were standing there with me, sharing our cup of morning coffee, just as we used to.

After taking the gondola ride into Telluride, the students and faculty plunged into our work of expanding our knowledge in the field of patient safety. We watched a documentary outlining the tragic case of Lewis Blackman, a 15-year-old boy who died due to medication error, miscommunication, and assumptions made by his medical team. The film explored the errors in Lewis’s care that have become far too common in our medical system: the lack of communication between providers and families, the establishment of “tribes” within medicine who do not collaborate or communicate with one another, the lack of mindfulness of the providers, and the culture in which all of these errors were permitted to happen.

But what resonated with me the most were the feelings described by Lewis’s mother. She defined her experience as one of isolation and desperation. “We were like an island”, she said. There was no one there to listen to her concerns. Ironically, Lewis died as a result of being in the hospital, the one place where he could not get the medical care that he so desperately needed.

A pain hit my stomach as she said these words. My family also shared the feelings of isolation, uncertainty, and loss throughout my father’s stay in the hospital. After Lewis’s death, his mother was not contacted. Instead, she was sent materials about grieving and loss in the mail. After an egregious error occurred during my father’s medical care, a physician did not give us an apology, but a white rose by a nurse.

An interesting discussion arose after the film. Our faculty emphasized the need for physicians to partner with the families of the patients. This will create not only a team during the course of treatment, but will cultivate compassion, empathy, and trust in the case of a terrible event. I know that despite the growing number of “apology laws” that protect, and even mandate, physicians to apologize to families after catastrophic events, few physicians actually do apologize. This results in families feeling like the events were there fault. I can say from experience that this is a burden that you can carry with you for years to come.

As I got back to my room and put down my books, this conversation mulled in my mind. The death of my father has given me the fuel to pursue medicine and patient safety as my career. It has instilled in me passion, energy, and determination. Yet the one thing that I have not found in the nine years since my father’s death is forgiveness. Although I do not hold any one doctor or nurse responsible for the detrimental outcome in my father’s care, I have not been able to forgive the team for what happened. I have not been able to go back to that hospital. And as I sat on my beautiful bed in the mountains, I realized that I also harbored another feeling: fear. Fear of becoming a physician who does not practice mindfulness, who does not partner with my patients, who does not apologize for my mistakes. I am afraid that despite my best intentions, I will only continue the vicious cycle. A fear that I will allow my patients to feel as though they are “on an island”.

I put away my computer and got into bed. Lying awake, I took in the gravity of the day. I am so grateful to be here at Telluride among students and faculty who share my passion in patient safety. I could not have imagined a more perfect way to spend Father’s Day.

Continuing a Journey That Seeks High Reliability

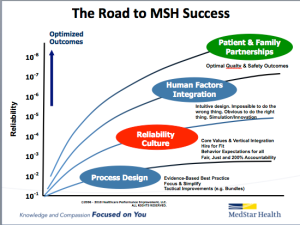

Posted: February 24, 2014 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership, Uncategorized | Tags: Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Healthcare, High Reliability Organizations, Just culture, Learning Culture, Poudre Valley Health System, Sentara Health, Transparency Leave a comment For the last twelve months, our health system has undertaken a system-wide initiative to join the ranks of healthcare organizations like Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Poudre Valley Hospital, and Mainline Health on a journey that seeks high reliability. We have already seen the fruits of this journey, and believe that when the benefits of a High Reliability culture are combined with the expertise provided by our National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, led by Terry Fairbanks MD, MS, along with the guidance provided by our National Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality and Safety, exciting opportunities to improve quality and safety while reducing cost can be realized.

For the last twelve months, our health system has undertaken a system-wide initiative to join the ranks of healthcare organizations like Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Poudre Valley Hospital, and Mainline Health on a journey that seeks high reliability. We have already seen the fruits of this journey, and believe that when the benefits of a High Reliability culture are combined with the expertise provided by our National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, led by Terry Fairbanks MD, MS, along with the guidance provided by our National Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality and Safety, exciting opportunities to improve quality and safety while reducing cost can be realized.

An important part of this journey includes creating a learning culture built on transparency that many in healthcare are still uncomfortable with. Overcoming these barriers requires consistent and repetitive role-modeling and messaging around core principles that help instill and reward open and honest communication in an organization. One of the ways we continue to reaffirm these important messages is through our “60 Seconds for Safety” short video series, which highlights different high reliability and safety principles. Each week, a video from the series is attached to our “Monday Good Catch of the Week” email, delivered throughout our system. The video highlights one important safety message all our associates can become more familiar with, and hopefully apply as they go about their daily work that week. Similar to starting every meeting with a safety moment, we want all of our associates to start each new week with an educational message reminding us that safety is our number one priority. The videos are available on MedStar’s YouTube Channel, under the Quality & Safety playlist. Please feel free to use any of these videos in your own Quality & Safety work — and please share ways you are getting the quality & safety message out to your front line associates.

The @DoctorsCompany Foundation Young Physicians #PatientSafety Award Now Taking Applications

Posted: December 6, 2013 Filed under: Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Safety, Uncategorized | Tags: AAMC, NPSF, Patient Safety, Telluride Student Summer Camps, The Doctors Company Foundation 2 Comments Because so many of our readers are compassionate young physicians, and physicians-in-training, we wanted to share another opportunity for you to showcase that passion and commitment for keeping patients safe. The Doctors Company Foundation, an organization that also sponsors a number of medical student attendees to participate in our Telluride Student Summer Camps, is partnering with the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) to offer The Doctors Company Foundation Young Physicians Patient Safety Award. The award will recognize young physicians for “their deep personal insight into the significance of patient safety work.”

Because so many of our readers are compassionate young physicians, and physicians-in-training, we wanted to share another opportunity for you to showcase that passion and commitment for keeping patients safe. The Doctors Company Foundation, an organization that also sponsors a number of medical student attendees to participate in our Telluride Student Summer Camps, is partnering with the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) to offer The Doctors Company Foundation Young Physicians Patient Safety Award. The award will recognize young physicians for “their deep personal insight into the significance of patient safety work.”

More information can be found, here on the NPSF website, or via The Doctors Company Foundation. A short summary follows:

Applicants are invited to submit essays that will be judged by a panel identified by NPSF. Six winners of this prestigious award will be selected and receive a $5,000 award, which will be presented at the Association of American Medical College’s (AAMC) Integrating Quality meeting in Chicago, June 12-13, 2014. Nominations must be submitted by 5:00pm ET, Monday Feb 3, 2014.

Eligibility:

- As of June 2013, applicants must be either a 3rd or 4th year medical student or a 1st year resident in hospital setting

- Award is for the best essay explaining your most instructional patient safety event during a clinical rotation-one that resulted in a personal transformation

- Award will be conferred by The Doctors Company Foundation in partnership with the Lucian Leape Institute at AAMC’s Integrating Quality meeting in Chicago

For an example of this year’s winning essays, click here. Please contact us or visit the websites if you have questions! We know there are many Telluride Alumni deserving of an award like this so please enter, and share the patient-centered care you are working so hard to make standard of care. Good luck!

A New Culture of Learning by John Seely Brown

Posted: January 11, 2013 Filed under: Education Technology, Leadership, Medical Education, Uncategorized | Tags: #edtech, John Seely Brown, Medical simulation 1 CommentIf you want to succeed, double your failure rate.

Thomas Watson, Founder–IBM

John Seely Brown, often referred to as JSB and former Chief Scientist at Xerox and Director of the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), co-authored A New Culture of Learning: Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change. In the book, JSB and Douglas Thomas, associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, discuss the need for learning in this century and beyond to be collaborative, welcoming questions, and challenging what we “know” to be answers. From the book:

John Seely Brown, often referred to as JSB and former Chief Scientist at Xerox and Director of the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), co-authored A New Culture of Learning: Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change. In the book, JSB and Douglas Thomas, associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, discuss the need for learning in this century and beyond to be collaborative, welcoming questions, and challenging what we “know” to be answers. From the book:

…in the new culture of learning the point is to embrace what we don’t know, come up with better questions about it, and continue asking those questions in order to learn more and more, both incrementally and exponentially. The goal is for each of us to take the world in and make it part of ourselves. In doing so, it turns out, we can re-create it.

The authors also talk about the need to embrace change, “looking forward to what comes next and viewing the future as a new set of possibilities, rather than something that forces us to adjust.” We don’t have to look very far to see the world changing much more quickly around us. The technology being developed is so intuitive, kids 5- and under can easily pick up an iPad or smart phone and navigate their way through the latest version of Angry Birds. JSB and Thomas provide examples of the 70 years it took from the discovery of a color TV signal in 1929 by Bell Labs to color TVs becoming ubiquitous in American homes, versus the exponentially faster adoption of internet technology (18% of households with internet access in 1997 to 73% in 2008). The tools we use in all business sectors, especially healthcare, are now more capable of harnessing large amounts of data that can drive solutions to questions that years ago may have seemed ridiculous, too “far out”, or even crazy.

So how does this all fit in medicine and medical education? The quote that led this post–“If you want to succeed, double your failure rate,” has no place at the bedside. But now, more than ever before, healthcare has a real need to solve the problems that are burying the industry with new thinking that comes from new learning. Simulation training and redesign of curriculum are two ways to address the needs not currently being met in medical education. But it goes deeper than that–as so many have said, the culture of medicine needs to shift. Medical students and residents have not only been bullied in their training by know-it-all mentors creating a learning environment that not only kills creativity, but the spirit as well. With all the discovery yet to be made in the sciences, how could one person think they “know” all the answers–wouldn’t it be best to view what is known as a starting place, and use it as a springboard to invite other intelligent, knowledgeable people into the conversation to take that baseline knowledge further?

In my maybe not-so-humble opinion, learning should embrace the not-knowing as well as the knowing. How we accomplish that in healthcare will take a shift–not only in thinking but in long-held beliefs as well. We don’t have the luxury of waiting for those afraid of change to leave medicine, and we don’t want to continue a stilted learning process that has proven to limit options. This change needs to be embraced today, and John Seely Brown’s book is both a lifeline and a roadmap. Please take a look at his keynote at Indiana University below, or pick up the book–I barely scratched the surface of the wealth of content contained within.

Happy Holidays and A Happy New Year!

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentTo all our readers:

Thank you for sharing in our passion for education and a safer healthcare system for all–

See you in 2013!

Culture of Respect In Medicine is the Responsibility of All Caregivers

Posted: October 12, 2012 Filed under: Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Education, Uncategorized | Tags: AAMC, Just culture, Leadership, Medical Education Leave a commentIn an excellent article, Darrell Kirch MD, President of AAMC, recently reminded all practicing physicians of the examples we set, and therefore responsibility we have, to our students when it comes to modeling a culture of respect in medicine. In his September post on the AAMC website, A Word From the President: Building a Culture of Respect, Kirch shares not only his own memory of being disrespected as a student, but also the results of the AAMC 2012 Graduation Questionnaire which shows that 33% of respondents confirm being humiliated by those in a mentoring role. Kirch comments:

When things like this happen, we compromise the learning environments of medical students and residents. Tomorrow’s doctors must be able to learn in a safe and supportive culture that fosters the respectful, compassionate behavior we expect them to show their future patients.

As physician educators, we have an opportunity to shape the culture of medicine. The disservice we do to our profession when we choose to break-down versus build-up our students, and one another for that matter, are missed opportunities to lead and provide a positive role model for those we are enlisted to enlighten. I remember a faculty member at one of the Telluride Summer Camps reinforcing that it’s not just disrespect down the power gradient, but peer-to-peer disrespect that also occurs in medicine. As such, it’s truly going to take educating the young on the “right way” to interact with colleagues, but also re-educating “the old” on tenets of professionalism and the impact disruptive behavior has in creating toxic safety cultures. And it’s going to take all of us to create the change needed and to challenge our peers who believe intimidation is part of the medical education learning culture. As Kirch points out:

As educators and leaders in the medical profession, we have an obligation to eliminate any mistreatment of medical students. The solution starts by addressing the culture and climate at each institution… at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine…implementing stricter policies and faculty workshops were somewhat effective…not sufficient by themselves. What is needed to eradicate medical student mistreatment is, they concluded, “an aggressive, multipronged approach locally at the institution level as well as nationally across institutions.”

In the end, no work environment should include humiliation and bullying. Other industries do not tolerate the disrespect medicine has been willing to accept for many years. Darrell and I have both referred to Dr. Pauline Chen’s piece in the NY Times, The Bullying Culture of Medical School and here on ETY, Bullying In Medicine: Just Say No, about how this negative sub-culture exists during training. Why would we accept this disruptive behavior by a few of our peers in a profession where caring and compassion is at the core of why we chose to pursue it? It’s counter-intuitive and, in the end, always reaches the patient–the person we have sworn to protect. Patients and families see this disruptive and professional behavior and wonder why it exists. Sometimes we have to hit bottom, look in the mirror, and say enough is enough. We need to acknowledge that the disruptive behavior of a small minority of our contemporaries reflects on all caregivers and our profession as a whole. I applaud Dr. Kirch and the AAMC for continuing to bring this unprofessional and unproductive behavior into the open–this is how change begins and care becomes safer for our patients.