MedStar SiTEL Achieves Accreditation by SSH

Posted: May 15, 2014 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Leadership, Patient Safety | Tags: Bill Sheahan, Medical simulation, MedStar SiTEL, Patient Safety, simulation training, Society for Simulation in Healthcare, Terry Fairbanks MD Leave a comment In direct opposition to last week’s tongue in cheek poke at Medical Simulation of Olde, according to leadership and Director of MedStar SiTEL (and Human Factors Center at MedStar Institute for Innovation) Terry Fairbanks, MD, MS (@TerryFairbanks) “When the mission is patient first, you don’t try first on patients.”

In direct opposition to last week’s tongue in cheek poke at Medical Simulation of Olde, according to leadership and Director of MedStar SiTEL (and Human Factors Center at MedStar Institute for Innovation) Terry Fairbanks, MD, MS (@TerryFairbanks) “When the mission is patient first, you don’t try first on patients.”

One of the increasingly obvious missing links between patient safety and medical education is the opportunity for students to learn their skills in a safe and controlled environment–and that means safe for both patient and caregiver. Simulation offers that option, and is growing across the country, as well as at MedStar Health in the Washington DC and Baltimore areas, offering an affordable, interdisciplinary, safety-driven and effective training ground for care providers young and old.

In fact, Bill Sheahan, Managing Director of MedStar SiTEL recently announced that their team achieved a milestone, putting them among the elite in medical simulation training. The group was recently granted accreditation by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare (SSH) in the areas of Teaching/Education and Systems Integration: Facilitating Patient Safety Outcomes. Achievement of this milestone required both a comprehensive application and a full-day site visit by three experts in the simulation field who had the opportunity to tour MedStar SiTEL’s Clinical Simulation Center in DC, meet with program and institutional leadership, MedStar Health’s experts in systems integration and patient safety, subject matter experts who offer education and training sessions in the simulation setting, and learners who have attended sessions at one of MedStar SiTEL’s simulation centers. The application/site visit process also provided a wonderful opportunity for MedStar SiTEL to reflect on all they currently do daily to improve patient safety, as well as to learn from experts in the field.

To date there are just 41 centers who have received accreditation by SSH. MedStar Health has had a very robust OB/GYN simulation program, led by Tamika Auguste, MD, in place for some time. In fact, we have mentioned her MOST (MedStar Obstetrical Simulation Training) program here on ETY (see The Future of Medical Education...). With the success of rolling out the MOST program across all MedStar entities with OB/GYN services, the SiTEL team is now in the process of implementing simulation education for additional disciplines across the health system, such as pediatric and cardiac critical care.

While most envision simulation training to include the lifelike, talking mannequins pictured above, some of the most critical training that occurs in healthcare simulation revolves around teamwork and communication. Because communication has repeatedly been shown to be the largest contributing factor to medical harm, the rehearsal of these skills could not be more pivotal. The debriefing that occurs after a simulation at MedStar SiTEL is key, and participants engage in the follow up discussion as though it had been an actual event. Having observed a number of simulation training exercises at MedStar SiTEL firsthand, the professionalism of the leadership team pre-event was equally as impressive as the commitment of the learners to participate as though the event was occurring in real-time. For more information on MedStar SiTEL services, click here.

Stay tuned for Stories of Simulation to come!

An Addendum to Annie’s Story

Posted: March 26, 2014 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Just Culture, Leadership, Patient Safety, Storytelling | Tags: Annie's Story, human error, Human Factors, Just culture, MedStar Health, National Center for Human Factors Engineering, systems approach, Terry Fairbanks MD, YouTube Leave a commentFollowing is additional information from our team who helped share Annie’s Story, led by RJ (Terry) Fairbanks (@TerryFairbanks), MD MS, Director, National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, MedStar Health, Tracy Granzyk (@tgranz), MS, Director, Patient Safety & Quality Innovation, MedStar Health, and Seth Krevat, MD, Assistant Vice President for Safety, MedStar Health.

We appreciate the tremendous interest in Annie’s story and wanted to respond to the numerous excellent comments that have come in over YouTube, blogs and email. The short five minute video sharing Annie’s story was intended to share just one piece of a much larger story–that is, the significant impact we can have on our caregivers and our safety culture when the traditional ‘shame and blame’ approach is used in the aftermath of an unintended patient harm event. At MedStar Health, we are undergoing a transformation in safety that embraces an all-encompassing systems science approach to all safety events. Our senior leaders across the system are all on board. But more importantly, we have nearly 30,000 associates we need to convince. Too often in the past, our Root Cause Analyses led to superficial conclusions that encouraged re-education, re-training, re-policy and remediation…efforts that have been shown to lack sustainability and will decay very shortly after implementation. We took the easy way out and our safety culture suffered for it.

Healthcare leaders like to believe we follow a systems approach, but in most cases we historically have not. We often fail to find the true contributing factors in adverse events and in hazards, but even when we do, we frequently employ solutions which, if viewed through a lens of safety science, are both ineffective or non-sustainable. Very often, events that are facilitated by numerous system hazards are classified as “nursing error” or “human error,” and closed with “counseling” or a staff inservice. By missing the opportunity to focus on the design of system and device factors, we may harm individuals personally and professionally, damage our safety cultures, and fail to find solutions that will prevent future harm. It was the wrongful damage to the individual healthcare provider that this video was intended to highlight.

In telling Annie’s story, we chose to focus on one main theme–the unnecessary and wrongful punishment of good caregivers when we fail to cultivate a systems inquiry approach to all unfortunate harm events. This is the true definition of a just culture…the balance between systems safety science and personal accountability of those that knowingly or recklessly violate safe policies or procedures for their own benefit. Blaming good caregivers without putting the competencies, time and resources into truly understanding all the issues in play that contributed to the outcome is taking the easy way out. We wanted our caregivers to know we are no longer taking the easy way out…

You will be happy to know that the patient fully recovered, that Annie is an amazing nurse and leader in our system, the hospital leaders apologized to her, and all glucometers within our system were changed to reflect clear messaging of blood glucose results. We believe we have eliminated the hazard that would have continued to exist if we had only focused on educating, counseling and discipline that centered around “be more careful” or “pay better attention”. We also communicated the issue directly to the manufacturer, and presented the full case in several venues, in an effort to ensure that this same event does not occur somewhere else.

This event, which occurred over three years ago, gave us the opportunity to improve care across all ten of our hospitals. It also highlighted the willingness of our healthcare providers to ask for help because they sensed something was not right and wanted to truly understand all the issues–they also wanted to find a true and sustaining solution to the problem using a different approach than what had been done in the past. Thanks to everyone for sharing your thoughts and for asking us to tell the rest of the story. We have updated the YouTube description as well.

And, thanks to Paul Levy for opening up this discussion on his blog, Not Running A Hospital, and to those of you who continue to share Annie’s story.

For those who have yet to see the video, here it is:

Taking the Easy Way Out When Errors Occur

Posted: March 21, 2014 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership | Tags: High Reliability Organizations, Human Factors, James Reason, Just culture, Leadership, MedStar Health, Terry Fairbanks MD Leave a commentHistorically in healthcare, when an error occurred we focused on individual fault. It was the simplest and easiest way out for us to make sense of any breakdown in care – find the person or persons responsible for the error and punish them mostly through things like shame, suspension or remediation. Re-train, re-educate and re-policy were the standard outcomes that came out of any attempt at a root cause analysis. Taking that route was easy because it didn’t require a lot of time, resources, skills or competencies to arrive at that conclusion especially for an industry that lacked an understanding, or appreciation of systems engineering and human factors. High reliability organizations outside of healthcare think differently, and have taken a much different approach through the years because they appreciate that it is only by looking at the entire system, versus looking to place blame on the lone individual, that they can understand where weaknesses lie and true problems can be fixed. James Reason astutely said “We cannot change the human condition but we can change the conditions under which humans work”.

The following short video is about Annie, a nurse who courageously shares her own story…a story that highlights when we didn’t do it right, but subsequently learned how to do it better by embracing a systems approach that is built on a fair and just culture when errors occur. A special thanks to Annie and to Terry Fairbanks MD MS, Director, National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare who helps us make sure our health system affords the time, resources, skills and competencies necessary to do it correctly.

Transparency in Healthcare: NYTimes Invitation to a Dialogue Continued

Posted: October 21, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Error, Transparency | Tags: Human Factors Engineering, MedStar Health, NYTimes, Paul Levy, Stephanie Wappel MD, Telluride Patients Safety Summer Camps, Terry Fairbanks MD 2 CommentsPaul Levy extended an open invitation to healthcare colleagues on the New York Times Opinion page in a letter to the editor entitled, Invitation to a Dialogue: When Doctors Slip Up. Here is an excerpt from that letter:

The tendency to assign blame when mistakes occur is inimical to an environment in which we hope learning and improvement will take place. But there is some need to hold people accountable for egregious errors. Where’s the balance?…People in the medical field are well-intentioned and feel great distress when they harm patients. Let’s reserve punishment for clear cases of negligence. Other errors should be used to reinforce a learning environment in which we are hard on the problems rather than hard on the people.

This has been a continued struggle, both spoken and unspoken, for years. As Paul points out, well-intentioned and hard-working physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other care team members come to work each and every day trying to help heal those in need. However, our current health care system fails them (and our patients) when they come to work. The system also fails to create a learning environment where well-intended caregivers can share potential areas of weakness or events because of fear for their own careers. Because the existing culture of medicine has been very slow to change, I have always believed that educating the young was a silver lining of sorts–or a way to rebuild our culture from the ground up. Educational content on open/honest communication with patients and colleagues has been the core curriculum at the Telluride Patient Safety Student & Resident Summer Camps for the last four years, and that has been shared with over 300 resident physicians, and medical, nursing, pharmacy and law student alumni. It was with great pleasure that I read Telluride alum, Stephanie Wappel’s following response to Paul’s NYTimes piece this weekend – one of the few selected from many responses (see additional comments, including MedStar’s Human Factors Engineering Director, Dr. Terry Fairbanks, & myself here):

I was fortunate to attend a conference on patient safety for which Mr. Levy was a faculty leader. I agree that we need to change the culture regarding the disclosure of medical errors. We cannot learn from what we do not know, and what we do not know can seriously harm our patients.

One strategy that has been implemented at my home institution is the celebration of “good catches.” Every Monday, all hospital employees receive an e-mail that features the “good catch” of the week, in which an error was detected and reported before it had the potential to cause harm. Any hospital employee can report these good catches.

They range from a nurse’s realizing she received the wrong dose of medication from the pharmacy to a medical student’s stopping her patient from getting a procedure that the physician thought he had canceled in the new electronic ordering system. Obviously, the institution is also working on discovering how that error occurred to prevent similar ones.

It is no easy task to change a culture, but this seems to be a good start.

STEPHANIE WAPPEL

Washington, Oct. 16, 2013

The writer is a resident physician at Georgetown University Hospital

The Good Catch Program Stephanie mentions has been a concerted effort of our Patient Safety team at MedStar Health to share some of the learning opportunities that arise on a day-to-day basis in healthcare, celebrate those for their courage to report them, and face them head on versus hiding from them.

If health care is to achieve safety successes seen in other high-risk industries such as aviation, we must learn to balance safety and accountability. For caregivers who knowingly and recklessly violate safe practice, discipline is the right course and much needed. But most errors that lead to patient harm occur because of bad systems or processes, not bad people. Until we can be open and honest about our mistakes, learn from them and support our well-intentioned colleagues, we will continue to struggle.

Formalizing Patient Engagement in High Reliability Seeking Healthcare Organizations

Posted: May 28, 2013 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Leadership, Patient Centered Care | Tags: H2Pi, HPI, Judy Ewald, Marty Hatlie, MedStar Health, National Center for Human Factors Engineering, Patient Engagement, Terry Fairbanks MD, Tracy Granzyk Leave a commentOver the past year, we have shared numerous posts on the characteristics of High Reliability Seeking Organizations (HRSO), and their drive to zero serious safety events (see Travel Buddies…, Reporting on Near Misses…, Mindlessness vs Mindfulness, and more). A number of healthcare organizations who have been on this HRSO journey for a number of years have experienced remarkable decreases in preventable patient harm across their system.

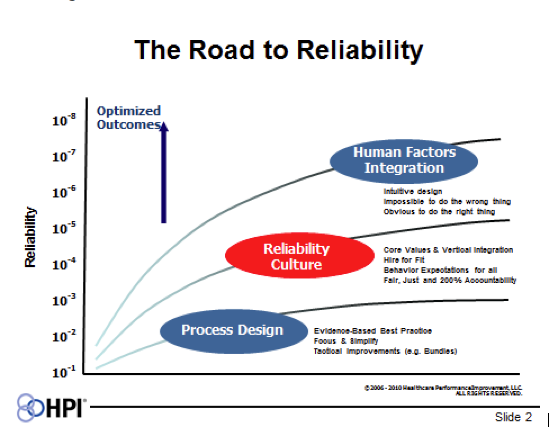

MedStar Health (MSH) is excited to be working with Healthcare Performance Improvement (HPI) on our own HRSO journey. By layering on the different “competencies” shown in HPI’s “Road to Reliability” diagram, it has been their experience that client hospitals can achieve higher levels of reliability. The diagram also highlights why we believe we can achieve a high level “Reliability Culture” at MedStar by integrating human factors engineering on top of all this work through our very own National Center for Human Factors Engineering led by Terry Fairbanks MD and his team of clinical care engineers.

MedStar Health (MSH) is excited to be working with Healthcare Performance Improvement (HPI) on our own HRSO journey. By layering on the different “competencies” shown in HPI’s “Road to Reliability” diagram, it has been their experience that client hospitals can achieve higher levels of reliability. The diagram also highlights why we believe we can achieve a high level “Reliability Culture” at MedStar by integrating human factors engineering on top of all this work through our very own National Center for Human Factors Engineering led by Terry Fairbanks MD and his team of clinical care engineers.

When I first saw this diagram, however, I immediately wondered what would happen to to the outcome curve if a fourth “competency”, patient engagement, was added. Was there a way to bring high reliability training and tools to our patients and families? In my mind, the best way to start this conversation was to have Marty Hatlie, JD, CEO-Project Patient Care, President-Partnership for Patient Safety, and one of our Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality and Safety (PFACQS) members, join us for an all-day High Reliability Boot Camp so he could add the patient’s voice into the training session, as well as share his thoughts with other PFACQS members. Carole Hemmelgarn, another of our PFACQS members, has already been working with the Children’s Hospital HRSO HEN network. Marty, as he always does, added a number of unique perspectives and new ideas to the high reliability discussions throughout the day, and those that have followed.

Here are a few of Marty’s thoughts that need to be shared. First, Tracy Granzyk, in her recent post, High Reliability Boot Camp, highlighted three things patients want: (a) Don’t harm me, (b) Heal me, and (c) Be nice to me. Marty astutely added two additional things patients want: (d) Listen to me, and (e) Give me the opportunity to engage and partner in my care.

Marty also pointed out that several of the safety and resilience training tools used by caregivers could also be customized and given to patients and family members. There would need to be some basic training but we believe this could be accomplished. HPI’s Judy Ewald, who was leading the day-long training session, underscored this point in sharing how she uses two tools – SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation) and STAR (Stop, Think, Act and Review) – in her personal life. Additionally, if we have Safety Coaches for our caregivers, why couldn’t we create Safety Coaches for our patients and families? Thanks to Marty, and to all those who added reminders on what patients want as we seek high reliability, I came away excited that we could take HPI’s outcomes curve on this diagram to a higher level.

High Reliability Boot Camp: Preparing for Zero Preventable Harm

Posted: May 22, 2013 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Leadership | Tags: HPI, Judy Ewald, MedStar Health, National Center for Human Factors Engineering, Terry Fairbanks MD 1 CommentMedStar Health is partnering with HPI (Healthcare Performance Improvement) to take this innovative health system to zero preventable harm utilizing the principles of high reliability organizations we have discussed previously on ETY (see Travel Buddies…, Reporting on Near Misses…, Mindlessness vs Mindfulness, and more!)

With the depth of data now available to patients, providers and administrators, it’s much easier for all to see how well we are doing and where our challenges exist in healthcare. And while data allows for benchmarking, reimbursement, transparency and more, Judy Ewald, Senior Consultant from HPI reminded all in the room that what patients want while in our care remains very simple:

- Don’t Harm Me

- Heal Me

- Be Nice to Me

Since the number one goal of all healthcare providers is to do no harm it would seem everyone is aligned. Not to mention, medical harm is costly — per HPI’s data, 16% of patients sampled who experienced an adverse event had increased hospital costs associated with that event, which amounted to $387M in a 2008 sample of Medicare patients. And that’s just the dollars and senselessness of it. Too many patients and families pay for medical harm with both mind and body. But this isn’t new information — we know this. So how do we change it?

HPI provides some tangible tools and a road map that health systems can turn to in order to embed a transparent culture of safety–a reliability culture, designed for safety that integrates human factors engineering making it intuitive for healthcare providers to do the ‘right’ thing, and harder to do the ‘wrong’ thing. MedStar Health, with its own National Center for Human Factors Engineering led by Terry Fairbanks MD, is poised to embed this crowning skill set into their high reliability journey.

Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH is part of the HPI family and provides an excellent example of the transparency high reliability seeking organizations also embrace along the way. The link above takes you directly to their external website, and an open discussion on their serious safety event rate. The video below models an excellent example of leadership around the type of transparency needed to be successful.

And finally, here are some key takeaways from Monday’s high reliability boot camp:

- The role of a leader in a safe and reliable culture includes: 1) Defining values & expectations; 2) Finding and fixing problems, and; 3) Reinforcing and building accountability

- Safety has to be the Number One organizational focus. No other agenda takes higher priority.

- A summary from the work of Edgar Schein, Society of Sloan Fellows Professor of Management Emeritus and a Professor Emeritus at the MIT Sloan School of Management — If you want to change culture, remember it will be a result of what your employees see you doing as a leader — the behavior you reward, the stories you share openly, how transparent you are as a leader and how you respond in the critical moments.

- Practice 5:1 Feedback with all associates — 5 positive reinforcements to every one negative.

- Communication is key. Find a tool that works and make it standard work. I liked SBAR.

- Situation (What’s the situation, patient or project?)

- Background (What’s the important information/problems/precautions?)

- Assessment (What’s your read of situation, problems/precautions?)

- Recommendation (What’s your recommendation, request or plan?)

If you too are on the journey to high reliability, we would love to hear about it! Please share the solutions and tools that have helped, and the challenges along the way.

Resilience Engineering: A Novel Approach to Keeping Patients Safe

Posted: April 10, 2013 Filed under: Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Safety | Tags: Human Factors, Keck Center of the National Academies, MedStar Health, Neil Weissman MD, Resilience engineering, Terry Fairbanks MD Leave a comment Following is information on another excellent educational opportunity offering a novel approach to keeping patients safe, coming up in June!

Following is information on another excellent educational opportunity offering a novel approach to keeping patients safe, coming up in June!

Terry Fairbanks MD, Director of the National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare and Neil Weissman MD, Director of the Health Research Institute, both at MedStar Health, are hosting a two-day, innovative and workshop-style conference to share knowledge, spark innovative ideas, and inspire new collaborations and partnerships to apply resilience engineering in healthcare.

The conference, entitled “Ideas to Innovation: Stimulating Collaborations in the Application of Resilience Engineering to Healthcare,” will be held on June 13-14, 2013 at the Keck Center of the National Academies in Washington, DC. Additional information and registration can be found at http://www.resilienceengineeringhealthcare.com.

What is Resilience Engineering and how is it used in Healthcare? Simply put, it is how individuals, teams and organizations monitor, adapt to, and act on failures in high-risk situations. In greater detail:

Resilience engineering is an emerging field of study that focuses on the fundamental systemic characteristics that enable safe and efficient performance in expected (and unexpected) conditions. It is a paradigm for safety in complex socio-technical systems, and its application to healthcare is very limited. During this two-day workshop, leading researchers and practitioners in resilience engineering and resilient health care will present a set of principles, practices and desired outcomes and products. After these presentations, attendees will be asked to initiate discussions that will lead to the development of an effective roadmap to catalyze the idea to innovation process – the ultimate goal is to help health care organizations and other interested parties improve quality and safety.

“Ideas to Innovation: Simulating Collaborations in the Application of Resilience Engineering to Healthcare” is hosted by the MedStar Health Research Institute and the University-Industry Demonstration Partnership (UIDP) as the first conference in UIDP’s Ideas to Innovation series.