Systems Approach and Just Culture Resonate at Doha Telluride Experience

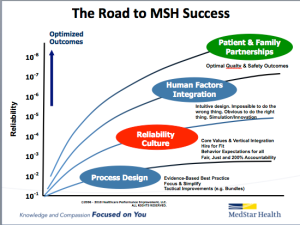

Posted: March 29, 2016 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Education, Medical Error, Patient Centered Care, Patient Safety, Storytelling, Transparency | Tags: Academy for Emerging Leaders in Patient Safety, Annie's Story, Healthcare Leadership, High Reliability Organization, Just culture, Seth Krevat MD, Telluride Patient Safety Summer Camps, The Doha Experience Leave a comment On day three of our Academy for Emerging Leaders in Patient Safety…the Doha Experience, Dr. Seth Krevat, AVP for Patient Safety at MedStar Health, led discussions on the importance of in-depth Event Reviews, Care for the Caregiver, and Fair and Just Culture approaches to preventable harm events. Seth shared the event review process used at MedStar Health which was designed by experts in patient safety, human factors engineering and non-healthcare industry resilience leaders. This event review process has been adopted by AHRQ and AHA/HRET, and has been incorporated into the upcoming CandOR Toolkit being released shortly to US hospitals.

On day three of our Academy for Emerging Leaders in Patient Safety…the Doha Experience, Dr. Seth Krevat, AVP for Patient Safety at MedStar Health, led discussions on the importance of in-depth Event Reviews, Care for the Caregiver, and Fair and Just Culture approaches to preventable harm events. Seth shared the event review process used at MedStar Health which was designed by experts in patient safety, human factors engineering and non-healthcare industry resilience leaders. This event review process has been adopted by AHRQ and AHA/HRET, and has been incorporated into the upcoming CandOR Toolkit being released shortly to US hospitals.

The young learners engaged in deep discussions around Fair and Just Culture – the balance between safety science and personal accountability. This topic followed interactive learning the previous day on human factors and system/process breakdowns. Similar to challenges we have in the US, the culture in the Middle East blames the individual first without a thorough understanding of all the causal factors leading up to an unanticipated event. After Seth showed the video, Annie’s Story: How A Systems Approach Can Change Safety Culture, and shared other case examples demonstrating how a good event review can disclose system breakdowns versus individual culpability, the young leaders gained a new appreciation of effective error reduction strategies. In the short clip that follows one of our young leaders, so empowered by the short three days with us, explains how she used what she learned to try to change her parents point of view on patient harm:

The passion and commitment of these future leaders to patient safety was inspiring for our US faculty, as well as for the leaders from the numerous Qatar healthcare institutions that participated in our sessions. I have no doubt this next generation of caregivers will be the change agents needed to achieve zero preventable harm across the world. We have seen many examples of their work already.

It was exciting to be in Qatar working collaboratively with others who are committed to “Educating the Young” as a powerful vehicle for change. Next stop for the Academy for Emerging Leaders in Patient Safety…The Sydney Australia Experience!

An Addendum to Annie’s Story

Posted: March 26, 2014 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, Just Culture, Leadership, Patient Safety, Storytelling | Tags: Annie's Story, human error, Human Factors, Just culture, MedStar Health, National Center for Human Factors Engineering, systems approach, Terry Fairbanks MD, YouTube Leave a commentFollowing is additional information from our team who helped share Annie’s Story, led by RJ (Terry) Fairbanks (@TerryFairbanks), MD MS, Director, National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, MedStar Health, Tracy Granzyk (@tgranz), MS, Director, Patient Safety & Quality Innovation, MedStar Health, and Seth Krevat, MD, Assistant Vice President for Safety, MedStar Health.

We appreciate the tremendous interest in Annie’s story and wanted to respond to the numerous excellent comments that have come in over YouTube, blogs and email. The short five minute video sharing Annie’s story was intended to share just one piece of a much larger story–that is, the significant impact we can have on our caregivers and our safety culture when the traditional ‘shame and blame’ approach is used in the aftermath of an unintended patient harm event. At MedStar Health, we are undergoing a transformation in safety that embraces an all-encompassing systems science approach to all safety events. Our senior leaders across the system are all on board. But more importantly, we have nearly 30,000 associates we need to convince. Too often in the past, our Root Cause Analyses led to superficial conclusions that encouraged re-education, re-training, re-policy and remediation…efforts that have been shown to lack sustainability and will decay very shortly after implementation. We took the easy way out and our safety culture suffered for it.

Healthcare leaders like to believe we follow a systems approach, but in most cases we historically have not. We often fail to find the true contributing factors in adverse events and in hazards, but even when we do, we frequently employ solutions which, if viewed through a lens of safety science, are both ineffective or non-sustainable. Very often, events that are facilitated by numerous system hazards are classified as “nursing error” or “human error,” and closed with “counseling” or a staff inservice. By missing the opportunity to focus on the design of system and device factors, we may harm individuals personally and professionally, damage our safety cultures, and fail to find solutions that will prevent future harm. It was the wrongful damage to the individual healthcare provider that this video was intended to highlight.

In telling Annie’s story, we chose to focus on one main theme–the unnecessary and wrongful punishment of good caregivers when we fail to cultivate a systems inquiry approach to all unfortunate harm events. This is the true definition of a just culture…the balance between systems safety science and personal accountability of those that knowingly or recklessly violate safe policies or procedures for their own benefit. Blaming good caregivers without putting the competencies, time and resources into truly understanding all the issues in play that contributed to the outcome is taking the easy way out. We wanted our caregivers to know we are no longer taking the easy way out…

You will be happy to know that the patient fully recovered, that Annie is an amazing nurse and leader in our system, the hospital leaders apologized to her, and all glucometers within our system were changed to reflect clear messaging of blood glucose results. We believe we have eliminated the hazard that would have continued to exist if we had only focused on educating, counseling and discipline that centered around “be more careful” or “pay better attention”. We also communicated the issue directly to the manufacturer, and presented the full case in several venues, in an effort to ensure that this same event does not occur somewhere else.

This event, which occurred over three years ago, gave us the opportunity to improve care across all ten of our hospitals. It also highlighted the willingness of our healthcare providers to ask for help because they sensed something was not right and wanted to truly understand all the issues–they also wanted to find a true and sustaining solution to the problem using a different approach than what had been done in the past. Thanks to everyone for sharing your thoughts and for asking us to tell the rest of the story. We have updated the YouTube description as well.

And, thanks to Paul Levy for opening up this discussion on his blog, Not Running A Hospital, and to those of you who continue to share Annie’s story.

For those who have yet to see the video, here it is:

Taking the Easy Way Out When Errors Occur

Posted: March 21, 2014 Filed under: Healthcare Innovation, High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership | Tags: High Reliability Organizations, Human Factors, James Reason, Just culture, Leadership, MedStar Health, Terry Fairbanks MD Leave a commentHistorically in healthcare, when an error occurred we focused on individual fault. It was the simplest and easiest way out for us to make sense of any breakdown in care – find the person or persons responsible for the error and punish them mostly through things like shame, suspension or remediation. Re-train, re-educate and re-policy were the standard outcomes that came out of any attempt at a root cause analysis. Taking that route was easy because it didn’t require a lot of time, resources, skills or competencies to arrive at that conclusion especially for an industry that lacked an understanding, or appreciation of systems engineering and human factors. High reliability organizations outside of healthcare think differently, and have taken a much different approach through the years because they appreciate that it is only by looking at the entire system, versus looking to place blame on the lone individual, that they can understand where weaknesses lie and true problems can be fixed. James Reason astutely said “We cannot change the human condition but we can change the conditions under which humans work”.

The following short video is about Annie, a nurse who courageously shares her own story…a story that highlights when we didn’t do it right, but subsequently learned how to do it better by embracing a systems approach that is built on a fair and just culture when errors occur. A special thanks to Annie and to Terry Fairbanks MD MS, Director, National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare who helps us make sure our health system affords the time, resources, skills and competencies necessary to do it correctly.

Continuing a Journey That Seeks High Reliability

Posted: February 24, 2014 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership, Uncategorized | Tags: Cincinnati Children's Hospital, Healthcare, High Reliability Organizations, Just culture, Learning Culture, Poudre Valley Health System, Sentara Health, Transparency Leave a comment For the last twelve months, our health system has undertaken a system-wide initiative to join the ranks of healthcare organizations like Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Poudre Valley Hospital, and Mainline Health on a journey that seeks high reliability. We have already seen the fruits of this journey, and believe that when the benefits of a High Reliability culture are combined with the expertise provided by our National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, led by Terry Fairbanks MD, MS, along with the guidance provided by our National Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality and Safety, exciting opportunities to improve quality and safety while reducing cost can be realized.

For the last twelve months, our health system has undertaken a system-wide initiative to join the ranks of healthcare organizations like Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Poudre Valley Hospital, and Mainline Health on a journey that seeks high reliability. We have already seen the fruits of this journey, and believe that when the benefits of a High Reliability culture are combined with the expertise provided by our National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, led by Terry Fairbanks MD, MS, along with the guidance provided by our National Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality and Safety, exciting opportunities to improve quality and safety while reducing cost can be realized.

An important part of this journey includes creating a learning culture built on transparency that many in healthcare are still uncomfortable with. Overcoming these barriers requires consistent and repetitive role-modeling and messaging around core principles that help instill and reward open and honest communication in an organization. One of the ways we continue to reaffirm these important messages is through our “60 Seconds for Safety” short video series, which highlights different high reliability and safety principles. Each week, a video from the series is attached to our “Monday Good Catch of the Week” email, delivered throughout our system. The video highlights one important safety message all our associates can become more familiar with, and hopefully apply as they go about their daily work that week. Similar to starting every meeting with a safety moment, we want all of our associates to start each new week with an educational message reminding us that safety is our number one priority. The videos are available on MedStar’s YouTube Channel, under the Quality & Safety playlist. Please feel free to use any of these videos in your own Quality & Safety work — and please share ways you are getting the quality & safety message out to your front line associates.

The Continued Quest for a True Culture of Safety

Posted: January 14, 2014 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership | Tags: Accountability, Bill Clinton, Just culture, Mark Chassin, Patient Safety Summit Leave a commentThe continued learnings that have come from the Asiana crash in San Francisco have reinforced one of the most important safety and quality issues affecting healthcare today–an existing culture that inhibits caregivers and support staff from holding each of us accountable and speaking up when we perceive a problem with patient care.

In a recent ETY post, Lessons Healthcare Can Learn From Asiana Flight 214, I shared the thoughts of Steve Harden as he applied the learnings from the Asiana crash to common weaknesses in patient safety. In a recent follow-up to his original piece, Harden reports on the interviews and investigations that have taken place since the crash last fall. He writes:

Though Captain Lee was an experienced pilot with the Korea-based airline, he was a trainee captain in the 777, with less than 45 hours in the jet. Captain Lee’s co-pilot on that fatal flight was an experienced instructor pilot who was responsible to mentor and monitor Captain Lee’s performance…(Lee) told investigators he had been “very concerned” about attempting a visual approach without the instrument landing aids, which were turned off. A visual approach involves lining the jet up for landing by looking through the windshield and using numerous other visual cues, rather than relying on a radio-based system called a glide-slope that guides aircraft to the runway.

…he did not speak up because other airplanes had been safely landing at San Francisco under the same conditions. As a result, he told investigators, “(he) could not say to his instructor pilot (that) he could not do the visual approach.”

What does this story have to do with healthcare? Harder emphatically shares that:

…after working with over 140 healthcare organizations, reviewing scores of root cause analyses, and conducting hundreds of real time observations in hospitals, clinics, ASCs, and labs – many of my experiences with healthcare staff sound just like Captain Lee’s interview. The culture in many of our healthcare organizations might as well have been created at Asiana.

This past weekend, I was an invited participant on the Culture of Safety Panel at the Patient Safety Summit held in Laguna Niguel, CA. The Summit was founded by Joe Kiani, the CEO of Masimo, and was keynoted by President Bill Clinton. It also included a number of thought leaders from across the country who came together with one common goal…Zero Preventable Hospital Deaths by 2020. During our panel, I posed the question, “If we as caregivers struggle to take collective professional accountability for safety concerns happening around us, who will? When we don’t stand up and share safety concerns about our patients with one another, we lose the most important element of any caregiver-patient relationship, which is trust.”

This past weekend, I was an invited participant on the Culture of Safety Panel at the Patient Safety Summit held in Laguna Niguel, CA. The Summit was founded by Joe Kiani, the CEO of Masimo, and was keynoted by President Bill Clinton. It also included a number of thought leaders from across the country who came together with one common goal…Zero Preventable Hospital Deaths by 2020. During our panel, I posed the question, “If we as caregivers struggle to take collective professional accountability for safety concerns happening around us, who will? When we don’t stand up and share safety concerns about our patients with one another, we lose the most important element of any caregiver-patient relationship, which is trust.”

In his article, Harden asks the question, “How would (your healthcare teams) answer this question?

In 100 out of 100 cases where it is needed, am I absolutely sure that my most junior and inexperienced staff member, when they perceive a problem with patient care, can and will have a stop-the-line conversation with my most senior and experienced physician?

At the Patient Safety Summit this weekend, Dr. Mark Chassin the CEO of the Joint Commission, asked the audience almost the same question Harden posed:

How many in the audience can answer yes to the following question (paraphrasing): If one of your junior staff members saw a potentially unsafe condition, how many of you are confident the staff member would “stop the line” and report that potential unsafe condition?

About 2-3% of the audience raised their hands. Dr Chassin confirmed that when he has asked the same question at other meetings, the responses are consistently between 0-5%, with no raised hands being the most frequent observation.

Harden’s article and the panel discussions on accountability this past weekend at the Patient Safety Summit took me back to the words of Dr. Sidney Dekker, a Professor of Humanities at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. Dr. Dekker has a PhD in Cognitive Systems Engineering and is the author of Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability:

Harden’s article and the panel discussions on accountability this past weekend at the Patient Safety Summit took me back to the words of Dr. Sidney Dekker, a Professor of Humanities at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. Dr. Dekker has a PhD in Cognitive Systems Engineering and is the author of Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability:

Calls for accountability themselves are, in essence, about trust. Accountability is fundamental to human relationships…Being able to offer an account for our actions (or lack of action) is the basis for a decent, open, functioning society.

The vast majority of caregivers want to do the right thing but the long-standing incentives and pressures to “look the other way” are powerful. To achieve a true safety culture, leaders need to be held accountable to removing these barriers and celebrating caregivers who raise their hand when safety concerns arise. Collective accountability can restore honesty and trust in our healthcare work place, and is essential to any healthy patient-caregiver relationship.

Returning Joy & Meaning to Healthcare Work in 2014

Posted: January 6, 2014 Filed under: Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Centered Care, Patient Safety | Tags: Alcoa, Healthcare, High Reliability Organizations, Just culture, Leadership, Lucian Leape, Patient Safety, Paul O'Neill, Telluride Patient Safety Summer Camp 3 CommentsThe success of our Telluride Roundtables and Summer Camps over the last ten years can be credited, in large part, to the generous time and participation of our faculty made up of patient safety leaders from around the world. The students and residents chosen to participate through the Telluride Scholars Program have been the beneficiaries of the knowledge and experience these great leaders and teachers all are so willing to share each year. Rosemary Gibson, Rick Boothman, Cliff Hughes, Kim Oates, Peter Angood, Kevin Weiss, Bob Galbraith, David Longnecker, Helen Haskell…the list goes on and on.

In the summer of 2011, students had the great fortune of working with Lucian Leape, who joined the faculty of our Telluride Patient Safety Summer Camp. It was an honor to have him with us, and something our alumni–young and old–will always remember. Lucian’s focus that week was managing disruptive behavior and returning joy and meaning to the healthcare profession. The photo included captures him in action doing what he does best–educating the young. As we begin a new calendar year still struggling with many of the issues Lucian called to light in his 1999 seminal work, I believe his teachings on Joy and Meaning in the workplace are more important today than ever before, and that those strategies will play an even greater role in preventing harm to our patients.

Caregivers at the frontlines consistently put considerable energy into achieving the highest quality, safest care possible for their patients in the face of considerable economic pressure and evolving healthcare models. We expect so much from our caregivers, and they far too often extend themselves beyond what is healthy–physically, emotionally and mentally–to meet the growing demands of the new healthcare. Lucian’s work on joy and meaning in the workplace is based on Alcoa leader Paul O’Neill’s premise that every employee should be:

- Respected

- Supported

- Appreciated

As healthcare leaders, we need to clear a safe path for all frontline associates to be respected, supported and appreciated. At the same time, we also need to eliminate the disruptive behaviors that have plagued healthcare for far too long. This year, a driving focus should be on ensuring those well intended healthcare professional are elevated, their humanness not only accepted but also protected through just culture approaches and human factor partnerships that mitigate and finally eliminate the potential for patient and employee harm while embracing a workplace built upon the high reliability foundations of a true learning culture.

As Lucian continues to remind us, it is our dedicated caregivers working at the bedside that need to feel safe — to know that their effort is appreciated and celebrated, that they have our support, and are respected for the work they do.

Pilots and Physicians…”Skin In the Game”

Posted: August 13, 2013 Filed under: Healthcare Quality, Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Education, Patient Safety | Tags: Just culture, Leadership, Not Running A Hospital, Patient Safety, Paul Levy, Pilots Leave a commentOver the past few years, I have really come to enjoy reading Paul Levy’s blog, Not Running A Hospital, especially when the focus is on quality and safety. I have found it educational, thought provoking, and timely. Paul’s post last Sunday, Kill this monster, was no exception, as he starts off by saying, “The time has come to drive a stake through the heart of an oft-repeated assertion. How often have you heard something like the following when those of us in healthcare who want to stimulate quality and safety improvements draw analogies to the airline industry?”

“Well, in an airplane, the pilot has an extra incentive to be safe, because he will go down with the ship. In contrast, when a doctor hurts a patient, he gets to go home safe and sound.”

His story took me back in time, as I remembered first hearing that comment many years ago. A pilot remarked similarly to me as we walked off a stage together, having just concluded an “Ask the Experts” patient safety panel at a national medical meeting. To be honest, I was a little offended, feeling as though I had just been insulted for being a physician. He had challenged the essence of why the great majority of us enter the medical field, which is to help others and always put our patients above our own self-interests. Before I could respond and defend my chosen profession, he was off…running to catch his plane. But his comment stuck with me and forced me to think deeper into why it bothered me. While it is true that similar complexities exist in both professions–high stress, high risk, varying conditions forcing both pilots and physicians to adapt–why do we, as healthcare professionals, struggle to grasp simple elements–those repeatedly passed on by human factors engineers–that aviation seems to easily adopt and follow without push-back?

His story took me back in time, as I remembered first hearing that comment many years ago. A pilot remarked similarly to me as we walked off a stage together, having just concluded an “Ask the Experts” patient safety panel at a national medical meeting. To be honest, I was a little offended, feeling as though I had just been insulted for being a physician. He had challenged the essence of why the great majority of us enter the medical field, which is to help others and always put our patients above our own self-interests. Before I could respond and defend my chosen profession, he was off…running to catch his plane. But his comment stuck with me and forced me to think deeper into why it bothered me. While it is true that similar complexities exist in both professions–high stress, high risk, varying conditions forcing both pilots and physicians to adapt–why do we, as healthcare professionals, struggle to grasp simple elements–those repeatedly passed on by human factors engineers–that aviation seems to easily adopt and follow without push-back?

I first thought about my specialty – anesthesiology. Why is it that many surgeons will tell anyone who is willing to listen that anesthesiologists are overpaid. They complain that many of us read newspapers, answer emails on our handhelds, or talk on our cell phones with friends while a case is in progress. Would an airline pilot ever consider reading the newspaper, answering emails or using their personal cell phone while working in the cockpit?

How about the accepted practice of running our anesthesia machines through a set of safety checks before using them each morning for surgery? While the manufacturers have added many self-check features through the years, there are still a few things we as anesthesiologists are asked to do each morning. Unless things have drastically changed in recent years, this “recommended safety practice” is not being followed regularly, the assumption being the machine worked fine yesterday so it should be ok today. Would an airline pilot ever think of not doing a pre-flight, airplane walk-around, checking the plane he or she is about to fly, and instead say, “Lets skip the pre-flight walk-around this afternoon…the plane was flown earlier today and I am sure nothing happened during the previous flight”.

Wrong-sided anesthesia blocks have seen significant increases in the past few years as regional anesthesia has become an important element for pain management supplementation in the post-operative recovery period. With the Joint Commission mandating the use of human factor tools like pre-procedure site markings, time-outs, and the use of checklists designed to help eliminate the “humans will be humans and forget at times” factor, we still see over 90% of these wrong-sided, wrong-site, wrong patient procedures attributed to a lack of following Universal Protocol and the use of a checklist. Would a pilot ever think of saying “Let’s not do the pre-flight checklist today. The extra two minutes it takes to do it just kills my day”?

The same figures hold true for surgeons. Many refuse to use timeouts and checklists. They will be quick to point out they have never had a wrong-sided surgery in their ‘fifteen or twenty years of practice’ and don’t need to use these safety tools. As John Nance says, those are the physicians that scare him the most. They believe they are, and will always be, better than the rest of us who will under the right circumstances make a mistake when the holes of James Reason’s Swiss cheese all line up. Having interviewed a number of surgeons and anesthesiologists who were involved in a wrong-sided procedure, every single one of them said the same two things right after the event: (a) They never thought this could happened to them, and (b) They are always so careful. But after the event, they realize we are all human. So why do some physicians still choose not to adopt the same mindset as pilots, before a patient gets harmed?

If you believe Paul’s premise–that it isn’t because pilots have more personal “skin in the game” than physicians do (see More Skin in the Game…)–maybe it could be one, or a combination of, three of the following reasons why we see differences in safety adoption between pilots and physicians: (1) Physician autonomy, (2) Financial incentives, and (3) A lack of accountability by leadership in the face of less than “reckless” behaviors.

To be continued….

Culture of Respect In Medicine is the Responsibility of All Caregivers

Posted: October 12, 2012 Filed under: Just Culture, Leadership, Medical Education, Uncategorized | Tags: AAMC, Just culture, Leadership, Medical Education Leave a commentIn an excellent article, Darrell Kirch MD, President of AAMC, recently reminded all practicing physicians of the examples we set, and therefore responsibility we have, to our students when it comes to modeling a culture of respect in medicine. In his September post on the AAMC website, A Word From the President: Building a Culture of Respect, Kirch shares not only his own memory of being disrespected as a student, but also the results of the AAMC 2012 Graduation Questionnaire which shows that 33% of respondents confirm being humiliated by those in a mentoring role. Kirch comments:

When things like this happen, we compromise the learning environments of medical students and residents. Tomorrow’s doctors must be able to learn in a safe and supportive culture that fosters the respectful, compassionate behavior we expect them to show their future patients.

As physician educators, we have an opportunity to shape the culture of medicine. The disservice we do to our profession when we choose to break-down versus build-up our students, and one another for that matter, are missed opportunities to lead and provide a positive role model for those we are enlisted to enlighten. I remember a faculty member at one of the Telluride Summer Camps reinforcing that it’s not just disrespect down the power gradient, but peer-to-peer disrespect that also occurs in medicine. As such, it’s truly going to take educating the young on the “right way” to interact with colleagues, but also re-educating “the old” on tenets of professionalism and the impact disruptive behavior has in creating toxic safety cultures. And it’s going to take all of us to create the change needed and to challenge our peers who believe intimidation is part of the medical education learning culture. As Kirch points out:

As educators and leaders in the medical profession, we have an obligation to eliminate any mistreatment of medical students. The solution starts by addressing the culture and climate at each institution… at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine…implementing stricter policies and faculty workshops were somewhat effective…not sufficient by themselves. What is needed to eradicate medical student mistreatment is, they concluded, “an aggressive, multipronged approach locally at the institution level as well as nationally across institutions.”

In the end, no work environment should include humiliation and bullying. Other industries do not tolerate the disrespect medicine has been willing to accept for many years. Darrell and I have both referred to Dr. Pauline Chen’s piece in the NY Times, The Bullying Culture of Medical School and here on ETY, Bullying In Medicine: Just Say No, about how this negative sub-culture exists during training. Why would we accept this disruptive behavior by a few of our peers in a profession where caring and compassion is at the core of why we chose to pursue it? It’s counter-intuitive and, in the end, always reaches the patient–the person we have sworn to protect. Patients and families see this disruptive and professional behavior and wonder why it exists. Sometimes we have to hit bottom, look in the mirror, and say enough is enough. We need to acknowledge that the disruptive behavior of a small minority of our contemporaries reflects on all caregivers and our profession as a whole. I applaud Dr. Kirch and the AAMC for continuing to bring this unprofessional and unproductive behavior into the open–this is how change begins and care becomes safer for our patients.

A Just Culture Takes Courage and Time

Posted: October 5, 2012 Filed under: High Reliability Organizations, Just Culture, Leadership | Tags: High Reliability Organizations, Institute of Medicine, Just culture, Reporting Culture, Virginia Mason Institute, Virginia Mason Medical Center 3 Comments I recently spoke with Diane Miller, VP & Executive Director of the Virginia Mason Institute about what it takes to change the culture of a healthcare organization in order to reach high reliability. She spoke of leadership and of teamwork–but she also mentioned courage. If, on any given day, 1 of the 30 leaders at Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) needs a supportive boost to overcome an obstacle challenging their hospital pointed true north in the patient’s best interest, the well-established just culture at VMMC ensures that one of the other 29 leaders will pick that person up–the team never losing stride. They have honed a collective courage, and have one another’s back, as the saying goes. The journey then continues, all now stronger for having overcome the challenge together.

I recently spoke with Diane Miller, VP & Executive Director of the Virginia Mason Institute about what it takes to change the culture of a healthcare organization in order to reach high reliability. She spoke of leadership and of teamwork–but she also mentioned courage. If, on any given day, 1 of the 30 leaders at Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) needs a supportive boost to overcome an obstacle challenging their hospital pointed true north in the patient’s best interest, the well-established just culture at VMMC ensures that one of the other 29 leaders will pick that person up–the team never losing stride. They have honed a collective courage, and have one another’s back, as the saying goes. The journey then continues, all now stronger for having overcome the challenge together.

It’s well documented in the literature, that the existing culture of a healthcare organization is an indicator of the challenges that will lie ahead on the high reliability journey. According to James Reason, existence of a just culture is one of four subcultures it takes to ensure an informed culture, a safe culture–one that maintains “…states of wariness…to collect and disseminate information about incidents, near misses and the state of a system’s vital signs” (Weick & Sutcliffe’s Managing the Unexpected 2007). According to Reason, the sophistication of error reporting that contributes to an informed culture requires a level of trust throughout an organization that overcomes controversy–that is courageous. The three subcultures Reason believes an informed culture also includes are:

- Reporting culture—what gets reported when people make errors or experience near misses

- Flexible culture—how readily people can adapt to sudden and radical increments in pressure, pacing, and intensity

- Learning culture—how adequately people can convert the lessons that they have learned into reconfigurations of assumptions, frameworks, and action

Patrick Hudson, a psychologist who has done extensive and notable work in the oil and gas industry, and has published a number of papers on high risk industries, shares a model of cultural maturity in his article, Applying the lessons of high risk industries to health care (Qual Saf Health Care 2003 (12):i7-i12). His adapted model shows a safety culture to be evolutionary, moving up from:

- Pathological: safety is a problem caused by workers. Main drivers are the business and the desire not to get caught.

- Reactive: safety is taken seriously only after harm occurs.

- Calculative/Beaurocratic: safety is imposed by management systems, data is collected but workers are not on board.

- Proactive: workforce starts to embrace the need for improvement and problems found are fixed.

- Generative: there is active participation at all levels of the organization; safety is inherent to the business and chronic unease (wariness) is present.

According to Hudson, organizations with an advanced safety culture possess the following qualities, he refers to as dimensions:

- It is informed

- It exhibits trust at all levels of the organization

- It is adaptable to change

- It worries

Moving an organization through the cultural evolutionary continuum, to an advanced safety culture is not an overnight task. In fact, during our conversation, Diane also reminded me that the journey to achieve VMMC’s level of success took time. Time and courage in a day and age where quick fixes and status quo no longer work, but are challenging to change. But both time and courage will be necessary to address the culture change needed in medicine, and recently called for in the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on September 6th. VMMC was mentioned during the IOM webcast covering the report, as an example of the bold leadership it took to get to where they are today, and where others will soon need to follow. (More information on the recent IOM Report can be found here).